Eliel Saarinen’s railway station as setting for New Eliel competition

The ongoing architectural competition for the re-development of Asema-aukio and Elielinaukio squares seeks ideas for infill construction in key spaces in the heart of Helsinki. These historically valuable urban areas around Eliel Saarinen’s Central Railway Station were developed in the early decades of the 20th century. In addition to connecting the station functionally with the city and its life, they also express the underlying values in Eliel Saarinen’s architecture and city planning and the development of his ideals.

In the Finnish urban tradition, open squares are important public spaces. 17th century city planners often situated squares in the heart of the new towns, built on a grid plan. These cities form today the network of historical towns in Finland. Due to legislation, central squares came to function as nodes of trade, administration, and social and public life, forming undeniable centre points of towns. Torille! See you at the square! is a cry one hears even today in Finland. The invitation is universal, the place and sense of community springing to life again. In designing the railway station, Saarinen gave a new architectural form to the tradition of squares, both aesthetically and in terms of the urban fabric. Among the many squares in Helsinki, the ones around the Central Railway Station have a distinct history and meaning.

Railways first had an impact on the growth and functions of Helsinki in the 1860s, with the opening of the line between Helsinki and Hämeenlinna. Railways served the industrialising capital and its trade and transport, and linked them to the inland waterways in the Häme province. The railway was a national project and a state-owned enterprise, rather a rare arrangement in Europe at the time.

The Central Railway Station was located on the outskirt of the city, on land reclaimed from Kluuvinlahti bay. The four new city blocks built there in the course of the 1830s–1870s came to accommodate public buildings and industry, with one of the city’s most popular wells in the centre. Two of the northernmost blocks were reserved for the railway: one for the station, the other for the adjacent open square. The pavilion-like terminus was located at the edge of its block, next to the platforms, with an undeveloped area on its east side.

Photo: T. Kanerva, 1960 / Helsinki City Museum

The rail network expanded rapidly. A particularly important line, one that linked Helsinki with St Petersburg, opened in 1870. It was built in cooperation with Russian railways and functioned as the trunk line of the Finnish rail network. In a few decades, the lines connected to this main route covered large areas of Finland, from Hanko to Kainuu. As it expanded, the railways also came to define a new national entity. The economy burgeoned in the wake of the expansion, with industry, communications, administration and the military all constructing a modernising Finnish society on an entirely new scale.

The St Petersburg line significantly affected eastern Finland in particular. Migration in the late 19th century led to the formation of a large Finnish community in St Petersburg; in terms of population, it was the second-largest Finnish town after Helsinki. St Petersburg played a crucial role in the life of Eliel Saarinen as well. A few years after the completion of the railway line, Saarinen’s family moved to St Petersburg, where Eliel’s father served as pastor of Ingrian parishes in the suburbs. Eliel grew up in the circles of St Petersburg, influenced heavily by the teeming and glamorous metropole, and such impressions would later show up in his work. School and studies brought him back to Finland, first to Tampere and then to Helsinki, where a successful career as architect got off to a flying start.

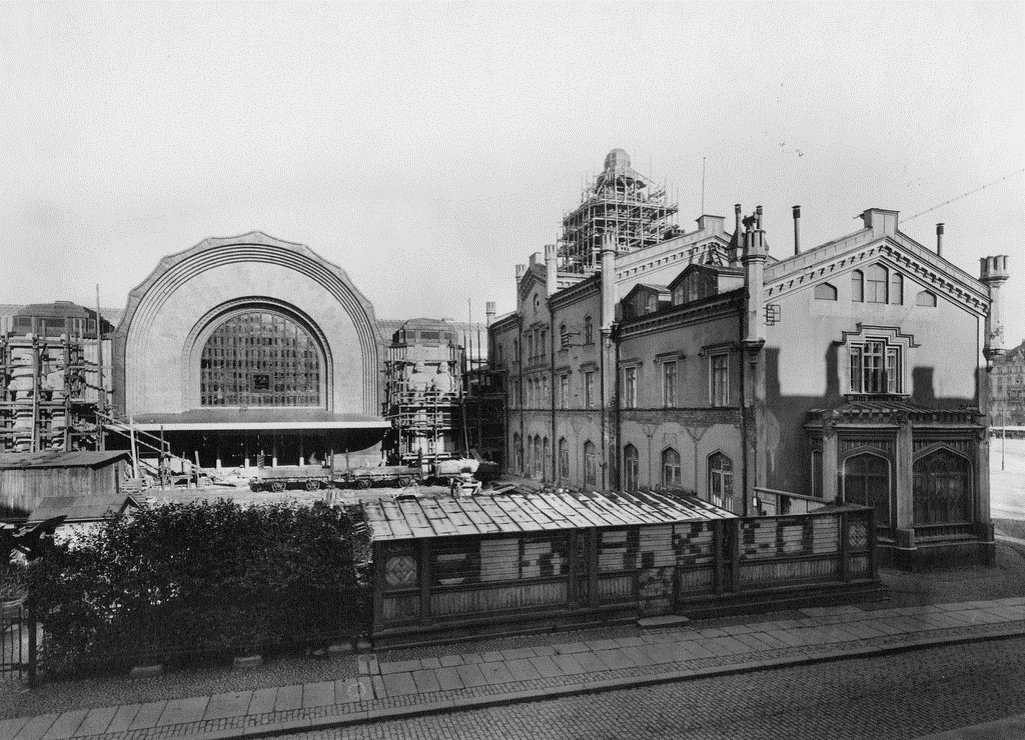

The connection with St Petersburg was also reflected in the architecture of the Central Railway Station in Helsinki. The old railway pavilion of the 1860s was part and parcel of the architecture of the Helsinki–Hämeenlinna line, whereas the terminus of the Helsinki–St Petersburg line was expected to display an impressive and wholly different continental architecture. The aims of the 1903–1904 architectural competition for the new station were laid out by the Club of Architecture and the design brief by the National Board of Railways. The winning entry by Eliel Saarinen and his associates acquired its final shape in stages. The monumental station was inaugurated in 1919, in the novel days of newly achieved independence.

The long design period marked a radical turning point in Saarinen’s architectural style. From the romantic use of natural forms and castle aesthetics, Saarinen’s architecture turned now towards a plastic monumentality, a new architectural expression. The façades of the railway station were given structurally impressive stone cladding, and the concrete vaults in the interior are magnificent. Ornamental decorations elevated the experience of travelling to festive and modern heights. The painting of a view from Koli on the wall of the first-class waiting hall was a reminder of the aesthetic, cultural and economic aspects of new Finnish identity, executed with innovative impressionistic techniques developed recently in European art.

The turn in Saarinen’s architectural style was influenced by the preparatory travels he made to study railway architecture in Europe. Designs he made around this time for the Peace Palace in the Hague and the Finnish Parliament served as a laboratory for his new style and ideas of scale. In the course of designing the railway station, Saarinen also won acclaim as an expert in modern urban planning. He served as designer and consultant in the development of the cities of Budapest, Tallinn and Canberra, followed by drawing up – with the support of local business interests and landowners – far-reaching plans for Helsinki, initially for Munkkiniemi–Haaga and a plan for Greater Helsinki. All this took place concurrently with the design and construction of the Central Railway Station. The rail network was at the heart of Saarinen’s ideas for the development of Helsinki, both his vision for the railway station of Pasila and the plan for rail connections to the suburbs, though he himself was unable to predict the time frame for the construction.

Following the ideas of 19th century Viennese architect Camillo Sitte, the surroundings of the station were developed with a firm hand. Sitte emphasised the importance of the dynamic between architecture and the surrounding urban fabric as a foundation for the creation of harmonious urban spaces and architecture. The entire Central Railway Station area became a textbook example of the spatiality of architecture in Helsinki. The architecture of the station is also significant from an international perspective.

The station, with its volumes and tower, linked with the adjacent spaces on three sides of the building. The new main façade turned towards Kaivokatu, where the old station building was demolished during the construction of the new one. The street itself was widened to create an open square with greenery in front of the station. Buildings in the Hilleri block to the west of the station were all demolished in the 1920s to make room for the new Asema-aukio square. The square connected to the station via its western entrance while providing a diagonal view towards the station’s main façade from Mannerheimintie. The northern boundary of the square found its place with the realignment of Postikatu, flanked by the Postitalo building. Having formerly sat perpendicular to Mannerheimintie, the street was now reoriented to run perpendicular to the station. The harmonious relationship between the Central Railway Station and surrounding urban spaces was defined spatially and functionally by the chain consisting of the Railway Square, Kaivokatu and Asema-aukio.

Photo: Erik Sundström, 1914 / Helsinki City Museum

The changes affected more distant blocks as well. The curving Murtokatu street envisioned by Saarinen created a new main thoroughfare from the north in the 1920s. Instead of the Unioninkatu monumental axis, traffic was now directed into the heart of the city along Murtokatu, later renamed Kaisaniemenkatu. The development of Railway Square also included the re-development of Keskuskatu, which linked Railway Square with the two Esplanades. Because the re-developed Keskuskatu was significantly wider than the street in the historical layout, it also provided an opportunity for the development of vertical commercial architecture. Saarinen himself realised the first commercial building for the street. His plans are visible to this day in the City-käytävä passage that runs through the Soopeli block from the Central Railway Station to the Julius Tallberg building. The original layout of the passage continues to facilitate the movements of tens of thousands of pedestrians every day. All these connections were developed concurrently with the new railway building. From an area on the edges of the city, Saarinen’s Central Railway Station and its surroundings constituted a new centre of transport and urban life, one that has retained its status to this day.

When the planning began, areas to the west of the station were not yet covered by a town plan and for a long time remained in industrial and railway use. For several decades, this situation afforded a direction for the extension of the city’s centre. The first person to create plans for the area was of course Eliel Saarinen himself, with his plan for Greater Helsinki, which featured a new, princely boulevard extending from Asema-aukio towards Pasila. The vision to extend in the Töölönlahti direction remained, although the status of central monument was taken instead by the Parliament Building constructed in Töölö. In his plans for the city in the 1920s, Oiva Kallio developed the monumental Töölönlahti axis as an administrative centre and a business hub, whilst the Central Railway Station with its surroundings remained separate and intact. Construction of the Postitalo building in the late 1930s took into account the view towards the railway station, and together with the Sokos building it defined the scale and character of the Asema-aukio space. The wedge-like layout apparent in plans from the 1920s is expressed by the orientation of Postitalo and remained in Alvar Aalto’s plans for the city centre in the 1960s, in which Töölönlahti was reserved as a park surrounded by cultural buildings.

Photo: Veljekset Karhumäki Oy, 1939 / Helsinki City Museum

The building of Restaurant Vltava may seem lonely today, but it was originally a warehouse and part of the extensive railway yard, with its engineering shops. Today, it is the last vestige of the industrial heritage of the entire Töölönlahti area, which has since been replaced during urban development. Dating from 1909, the Vltava building is also the oldest part of the Central Railway Station. Designed by the Board of Railways, the building’s design history differs from the rest of the station as designed by Saarinen. The warehouse was a utility building, but as the northern marker of the Asema-aukio square it was given a controlled architectural exterior. The atypical orientation of the understated western façade of the building is a throwback from the layout of the area prior to the railway station, which aligned anew its streets and blocks.

The yard beyond the warehouse served the repair workshop and the goods station, its openness dictated by practical considerations. The architecture of the its façade nevertheless has a defining spatial effect, which is today apparent in the current Elielinaukio square, formed when the former goods station was redeveloped into a passage with shops in the early 2000s.

The purpose of the ongoing design competition is to explore possibilities for infill construction in the open spaces on the west side of the railway station. The history and status of these areas are firmly associated with the station and its monumental architecture. The monumental status of the Central Railway Station does not arise from its dominant scale – on the contrary, its volumes are often lower than those of the surrounding cityscape – but from the dynamic between the architecture and its setting, which in turn has a direct bearing on the character of that monumentality. Such vital spatiality makes the area sensitive to any change.

The open squares next to Saarinen’s railway station are established urban spaces, the fact of which has elicited critical voices regarding the feasibility of infill construction in the area. Guidelines for the redevelopment of the area cannot be found in the height or efficiency of existing buildings but in the urban spaces and their relationship with architectural elements. From the viewpoint of the urban environment, this is the legacy of Saarinen’s architecture, and it is important that it be preserved. The cultural environment around the Central Railway Station carries exceptionally loaded meanings that are valuable even internationally. What the Elielinaukio competition has to offer for the preservation of this legacy remains to be seen.

Mikko Lindqvist, Helsinki City Museum, Cultural environment team, architect SAFA